ASCI Conversation: Hazal Corak and Ram Itani

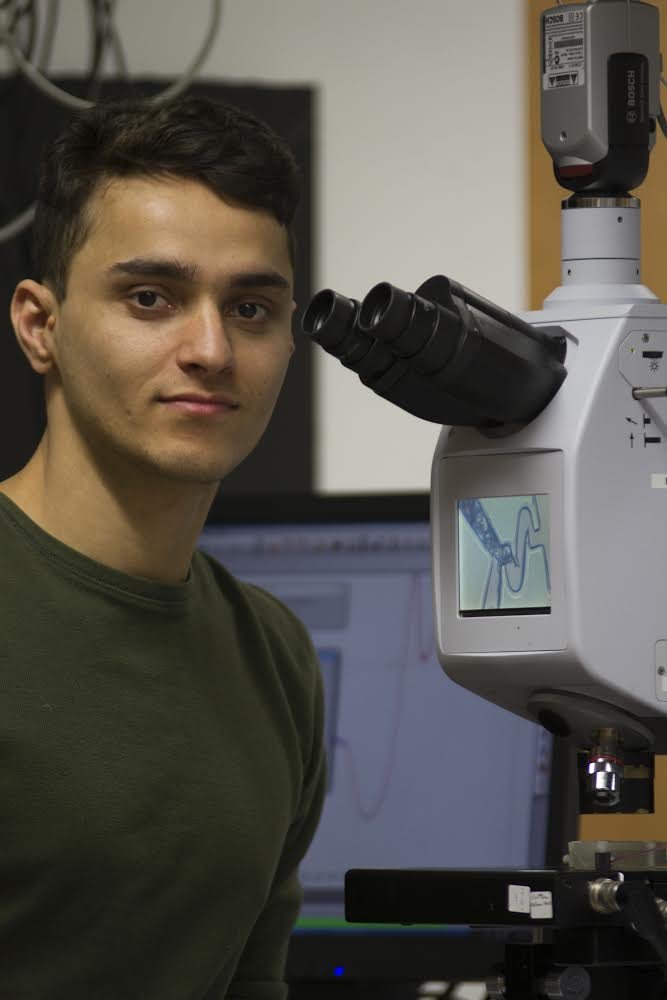

Familiarizing the Unfamiliar: A Conversation between PhD students and ASCI Graduate Fellows Hazal Corak and Rami Itani

By Lee Jasperse

Lee Jasperse: Can you give a brief description of your academic projects?

Hazal Corak: I’m an anthropologist in my third year at the University of Chicago. I’m from Turkey. My project focuses on the scrap metal recycling industries in Turkey, situated along the shores of the Aegean Sea. I am working on global flows of waste and money in relation to one another.

Ram Itani: I am a fourth-year student in physical chemistry. I’m developing a technology to study the fundamental processes of DNA hybridization. What I’m trying to understand is this: when two separate strands of DNA come into contact, how do they merge together to form the famous double-helix structure we’re all familiar with? In order to study this, you have to bring together two strands of DNA really rapidly. I’m developing a fast mixing technology to do this in laboratory conditions. It’s based on “microfluidics,” which means manipulating fluids on a very small scale. What I design and fabricate are very small channels—channels smaller than a strand of hair—and then I push fluid mixed with DNA through those channels and watch the DNA using infrared spectroscopy to see what happens.

Lee: Both of your projects seem to have to do with manipulating and transforming materials. Did being ASCI fellows this year allow you to discover common interests across disciplines?

Ram: For me, what has been the most rewarding as a fellow is getting to see what other people in non-science fields are doing—people like Hazel. It’s very uncommon for us in the physical sciences to interact with non-scientists. As a fellow, I got to understand the thought processes behind the work people are doing in arts and social sciences. At the same time, non-science fellows have asked me about my thought process. Ultimately, we’re all interested in problem-solving and get to offer each other advice from different perspectives. One fellow, for example, offered me advice from ancient Chinese art on fabricating the channels I’m working on. Thinking with these other viewpoints has pushed me to rephrase my own research so that others can understand and engage with it.

Hazal: I ended up developing my project through an engagement with monuments—how they’re built, and how they’re destroyed, especially in post-communist contexts like Hungary. A lot of these monuments that are displaced end up finding new places in amusement parks. But many others of them go to scrap metal factories to be recycled into construction materials. So my research examines how the products of artistic fields end up in scrap piles, to be taken up by engineers. As part of my research, I go to factories to meet with engineers. I focus on their process. When I observe what they’re doing, though, I don’t get a chance to talk to them about my project. This fellowship has allowed me to get feedback on my project from scientists and engineers—those people who have a notion of working with materials from a different point of view than artists and social scientists.

Another value of the fellowship is something that Julie Marie keeps emphasizing, which is stealing metaphors from other fields. I find it totally liberating. I’m inspired, for example, learning about a musician’s work process, what metaphors energize her work, how such metaphors can refract my vision of my work in new ways. A main motto of anthropology is: defamiliarize the familiar and familiarize the unfamiliar. The ASCI fellowship provides the opportunity to do just that.

Lee: What are the advantages of having to describe your methodology to people whose methodologies are very different from your own?

Hazal: When I first had to describe anthropological methodology to other fellows, the first thing that happened to me was finding our methodology so absurd. Talking across disciplines requires a process of translation, of defamiliarizing the familiar. And then you have to try to make it sound not so absurd by putting your research in terms that make sense to people outside your field. We need to have these conversations to develop terms that can bridge different fields.

Ram: One of the things I learned was that scientists are very bad at communicating, especially to audiences outside of science. I realized scientists have to do a better job communicating with one another and with those outside science. We often use terms that are so familiar to us that we don’t explain them in great detail to others. We assume a lot of things are clear to a general audience, and they’re really not. Presenting as a fellow forced me to explain things that would be clear to a high schooler, for example. I find that other fields are much better at doing that.

Lee: In what ways has the fellowship impacted your work?

Ram: I’ve always been fascinated with cross-disciplinary research. One of the reasons I applied for this fellowship is that about five years back I was doing an internship for the Indianapolis Museum of Art. I worked with the scientist who runs their conservation sciences lab. They ran into a problem of not understanding where this specific ancient piece of art came from. It had writing that looked almost like Sanskrit. I was asked if I could help figure out the origins of art piece. What they were asking for was the cultural context. As a scientist, I can tell you about, for example, what’s in the ink, but not so much about the cultural context. To understand the cultural context, you have to go beyond the physical sciences. Doing the ASCI fellowship, I was able to talk to people from the arts to better understand the cultural context for this piece of art. In the last five years, I hadn’t made headway in locating the artwork’s cultural context. But because of this fellowship, I got a decent lead as to where this artwork came from. I talked to experts from Southern Nepal, where we previously thought this work may have come from. The Nepalese experts told us the work didn’t come from Nepal but gave us a lead to a certain part of India as its place of origin.

I offer that tangent to say that this fellowship gave me insights that had I only been surrounded by scientists, I wouldn’t have had the encouragement to pursue. Down the road in academia, I’ll always be looking for opportunities to cross disciplines.

Hazal: There is something so instructive in engaging with artists. Anthropologists say things about people who do things. Artists are actually doing things. Seeing how people get playful with their work inspires me. The second part of the fellowship, which we’re about to proceed with, will have us doing a project outside of our field. I’m thinking about doing metalworking workshops so that I can have an embodied experience of what I’m studying in my anthropological research.

Lee: Can you say more about the value of playfulness as an inspiration to academic work, or to enduring the long haul of academic work? Ram, does playfulness come into your work?

Ram: It’s hard to add playfulness to the type of chemistry that I do. What I do is really more of physics than chemistry. When you think of chemistry, you’re making stuff. With my work, we’re watching stuff happen in micro detail, which makes it difficult to incorporate playfulness.

Hazal: I think chemistry is such a playful field. Although I’m not a chemical engineer, I got inspired thinking about chemistry alongside Ram. Certain social science writers, notably Karl Marx, use chemistry metaphors playfully all the time. It gives you lots of metaphors to play with. Working with concrete matter is a very playful thing. Beyond this, though, you have to be playful with your words so that people can actually read and understand you. Play is the basis of human interaction. For me, it’s important to keep play alive as a researcher, in order to not be a boring person interacting with my interlocutors, in order to not seem like someone who’s just there to extract information from them. Playfulness allows you to actually become a part of their lifeworld. It’s not only an idea, it’s also an orientation toward life. You have to keep it alive as a researcher and also a writer. Humor, for example, is critical.

Previously I talked about how I was inspired by artists who include playfulness into their work. But the same goes for scientists. In the last fellowship meeting we had, we heard about our friend’s research—she’s a quantum engineer—who’s playing with diamonds. This got us talking about magic, which is a key concept in the history of anthropology but is also crucial to artists and scientists alike. Concepts like magic emerged as the basis for a common language we could forge across physical sciences, social sciences, and the arts.

Ram: I want to share a personal story. After this fellowship, I’ve realized you can be an artist even if you’re a scientist. Art can speak in different ways. I’m working on microfluidic devices. I’m the only one in my lab group that does this, so there is a lot of trial and error. For this project, I use an expensive special material called calcium fluoride windows, which are like glasses but much thinner. They’re incredibly fragile. I’m pressing them into heated things so they break incredibly often. Before ASCI, whenever they broke, I’d just throw the refuse out. But in the course of this internship, I realized each broken piece has a meaning. These are crystals, so they break in unique ways depending on if I drop them or if they cracked from being heated up. How each broken piece looks tells a story. Now that I’ve been an ASCI fellow, I’ve started collecting all the broken pieces. I have bags totaling about $500 so far in broken windows. At the end of my project, I want to create an art piece from these shattered pieces of crystal. Maybe I’ll call it “The Art of Failure.” I’ll glue these pieces on an acrylic piece and maybe gift it to my PI (principal investigator). Then all my failures will be a beautiful piece of art.

Hazal: This is a perfect manifestation of how our projects are entangled. Ram was talking about how scientists and artists can both engage with waste. This is the main question of my project: how do human societies engage with their waste? How are these relationships changing over the course of contemporary capitalism? What are the moral and political ramifications of these transformations? Ram just embodied the spirit of this project so well—how a scientist in contemporary capitalism might forge an alternative moral and artistic commitment to transforming and revaluing waste.

Ram: I think when you have an environment where we’re communicating, across disciplines, about our failures and our waste, there’s hope of coming up with something big at the end. A year ago, I would have just thrown these expensive artifacts of failure in the trash. Now, this waste can be transformed into materials that tell a bigger story.