“A Fairytale of Modern Infrastructure”:

ASCI graduate collaboration examines the complex history of Chicago’s water cribs

By Ellen Wiese

Reed McConnell (left) and Lily Scherlis, recipients of the ASCI Graduate Collaboration Grant. The 68th Street Water Crib is distantly visible on the horizon.

Visible on a clear day from Hyde Park’s Promontory Point, the distant shapes in Lake Michigan are often mistaken for an oil rig. But this metal structure, composed of what looks like two large cylinders connected by a metal beam, is the 68th Street Water Crib, one of nine of its kind offshore of the city of Chicago, two of which still fulfill their intended purpose.

“I had become, during Covid, kind of obsessed with them,” says Reed McConnell, PhD student in Anthropology at the University of Chicago. “I would go down to the Point, just trying to take walks and get out of the house, and I had noticed the 68th Street Water Crib. So I finally looked it up online and started to go into the wormhole of the history of the cribs.” Built between 1865 and 1935 and located miles from the shore, the cribs function essentially like gigantic vacuums, funneling water through tunnels beneath the lakebed to be processed for consumption in Chicago. “I wasn’t sure if it would ever turn into anything,” says McConnell, “and then it somehow came up in conversation with Lily and it turned out that she’d essentially done the same thing.” Lily Scherlis, a PhD student in English and Theater & Performance Studies, also lived a few blocks from the Point and had noticed the structure during the pandemic, her interest initially piqued by zooming in on Google maps and finding the cryptic label: Crib. “It turns out that, being who we are, we both had fixated on a weird piece of infrastructure,” Scherlis adds.

The cribs became a shared object of fascination for both Scherlis and McConnell and a frequent subject of conversation, but the partnership didn’t become official until McConnell, then a Graduate Fellow with the Arts, Science + Culture Initiative (ASCI), encountered the initiative’s Graduate Collaboration grants. “It suddenly hit me that we should take all of these conversations we’ve been having and thoughts we’ve been bouncing back and forth and turn it into something concrete,” says McConnell. “We got really excited about the idea of using the opportunity of a collaborative grant to create an art piece together.”

The ASCI Graduate Collaboration Grants are focused around building opportunities for transdisciplinary exploration between the arts and sciences. Four to six projects a year are provided up to $3,000 in funding for a group of two or more graduate students (at least one in the sciences and one in the arts) to explore a topic at the intersection of their areas of expertise. While these partnerships are often fruitful, the program focuses on process over product: a 2020 program evaluation by the independent research organization NORC at the University of Chicago found that even projects that did not culminate in a cohesive final project nevertheless “gave participants a window into previously inscrutable subjects, an opportunity to examine their own discipline with fresh eyes, and a platform for bridging institutional and disciplinary barriers.” In 2021, McConnell and Scherlis entered an application for the Graduate Collaboration Grants with the goal of creating a video-based ethnographic artwork exploring the logistics, politics, and aesthetics of urban infrastructure. Their application was successful, and they embarked on the year-long endeavor in fall of 2022.

Behind the scenes

The partnership between Scherlis (left) and McConnell has been characterized by serendipity, from their meeting in Berlin to their shared fascination with the water cribs.

The pair first met in Berlin, where McConnell was completing an MA in Cultural Theory & History and Scherlis was traveling on a fellowship. Although they didn’t realize it at the time, they had both recently applied to PhDs at the University of Chicago. After the two reconnected in Chicago and realized their shared interest in the cribs, they began investigating their function and history more deeply. In her research, McConnell found that the structures had been occupied by crib keepers, employees of the City of Chicago who lived and worked on the cribs for two-week shifts, often alone. “That was the moment we realized we had an interdisciplinary project, because to do this will involve ethnography, oral history, archival work—but also it’s such rich visual material and has the affordance of making the way that resources move through a city feel intuitive and visible,” says Scherlis. “We wanted to show how integral labor is, and how integral people’s lives are, to making cities run, because that’s a lot of what gets hidden or forgotten when people get obsessed with infrastructure as such.”

Scherlis is a writer and visual performance artist and studies labor and social performance in the twenty-first century. Just prior to the ASCI grant, she had completed a project on a sulfur pile in Calumet that incorporated video performance and writing components. “I was thinking about this stuff,” she says, “but from the perspective of aesthetics and the poetics of ecological disaster, and then also through the affordances of video and performance to connect elements of that to everyday life.”

McConnell is primarily an environmental anthropologist who focuses on apocalyptic landscapes. She studies the ways people interact with toxified ecologies and environmental disaster, “whether that’s a slow disaster, like the presence of some sort of chemical in the groundwater from a nearby plant, or whether that’s a more acute form of disaster, like an earthquake,” she says. This work extends to investigating the futures that people are able to imagine for themselves based both on their lived experiences and on the stories they consume. In her work, McConnell is interested in investigating the hidden aspects of modern life. “I’ve always been super fascinated by the places that you’re not supposed to go,” she says, whether that’s the just-visible water cribs of Chicago or the sprawling plants built next to rural highways, both deliberately distanced from population centers. “I’ve always thought of them as a behind-the-scenes of how certain kinds of life are produced,” she says. “What is this stuff I’m not supposed to be looking at, to understand materially the life that I’m living? For me, that’s always been specifically focused on geographical distribution and questions of infrastructure. It comes from an attraction to trespass, to a certain extent.”

Scherlis and McConnell utilized computer visualizations of infrastructure projects to express the uncanniness of the cribs.

As a visual artist, Scherlis was struck by the way the weirdness of the cribs—the tunnels under the lakebed, the design evoking oil rigs and circus tents, and the isolation of the water management workers living on them—estranges observes from what is often considered a mundane element of life. “Suddenly you start to think of a city, instead of as buildings and fun metropolitan things and streets and people, you think of it as all of these bodies that are motivated by money for survival or profit and are producing massive quantities of gunk that’s destroying the planet and causing all this complication,” Scherlis says. “And then you see that a person came up with an idea: let’s have some of those people dig massive tunnels, for miles, in order to create giant water vacuums that solve the issue of all of these bodies coming together to make waste. You start to experience life really weirdly when you look at that.”

A black box

Scherlis and McConnell initially planned to focus the project on the personal stories of the crib keepers, building the video around interviews with people who had worked on the sites. The cribs’ early history is full of dramatic stories of the harsh and often dangerous environment: around the turn of the century, a crib keeper had to don scuba gear and dive into frigid water in order to hack open a tunnel that had frozen closed and restore the water supply to the city. A few years later, in January 1909, a fire on a crib under construction led to the deaths and injuries of more than 50 workers.

Much of this information, as well as engineering information about the cribs’ construction, is publicly available. However, more recent information on the structures is highly regulated by the U.S. government. Civilian boats are not allowed in the waters near the cribs, and drones are not permitted within 500 feet. The reason for the high security, say Scherlis and McConnell, is the potential biosecurity threat to Chicago. “We can’t even visit the cribs, because someone could poison the water in the cribs if they visit,” says McConnell. “It makes it into this black box in a certain way, for purposes of preventing catastrophic futures.” Particularly since the 9/11 attacks, any details about the cribs—including their layout, personnel, and exact mechanism of operation—have been closely guarded. Over the winter, McConnell and Scherlis filed a number of requests for documents via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) from agencies including the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District and the Army Corps of Engineers. “All those requests came back empty,” says Scherlis.

As seen from the western shore of Lake Michigan, the 68th Street Water Crib looks like a cross between an oil rig and a circus tent.

Crib keepers, too, have proven hard to find. However, Scherlis was able to track down another useful source: longtime Chicago resident and owner and operator of a private sailing charter company Michael Blanchard. Known as Captain Mike, he has been invested in the water cribs in general and Four Mile Crib—the oldest crib, located 3.3 miles east of Monroe Harbor—for half a century. He now runs a conservation effort called Save Four Mile Crib focused on preventing the demolition and abandonment of the crib by the City and on devising ways to preserve, restore, and repurpose the structure. “He has these intense, profound depths of research into the cribs,” says Scherlis. “He knew more than anyone we’d encountered.”

During their conversation at the Chicago Public Library, they discussed the history and future of the cribs, Captain Mike’s decades of information-gathering, and a unique aspect of his preservation work: using his research and observations on the water, he has designed and built intricate paper-cut models of Four Mile Crib. “If we want to talk about methodology, it made me realize how many different possible relationships to research different people have,” says Scherlis. “This man is doing deeper research than most people I know at UChicago out of the basis of pure fascination with some aspect of city infrastructure. It opened up my sense of what scholarship can be, and how people relate to the world around them.”

A thread of fascination

As of February 2023, the project was in its material-gathering phase. McConnell had spent hours at archives, collections, and the UChicago library scouring resources including engineering guides, newspaper articles on crib construction and disasters, photographs, maps and diagrams, municipal reports, and public works records. Scherlis rented a 600mm telephoto lens and the two spent a cold day driving up and down Lake Shore Drive attempting to photograph the cribs. As part of thinking through all the different ways to visualize the project, Scherlis also compiled online images and screenshots from Google Maps alongside the filmed footage. “What working across methods is highlighting for me is that there’s this distinction between research and following a thread of fascination, and then looking with an eye towards product,” says Scherlis. “It’s really highlighted for me where the dotted lines are between those processes. I realize the ways in which I am responsible for collecting material that will visually instantiate what is also an intellectual journey for me and Reed.”

When they sat down with Captain Mike at the library, they both noticed the differences in the ways they approached the interview from the angles of their specific disciplines. “I was learning from Reed, if you’re sitting down with someone to get a sense of their experience, here is how you approach that,” says Scherlis. “And then there were certain questions that I asked that paid particular attention to formal constraints that come with the medium that I work in, and also from my particular kinds of attention to visuality and technology, that might not otherwise have come up.” But although the questions they are asking of their subjects and of the project in general may be different, they share a unified idea of the final product they want to produce. “It’s not a documentary, it’s not a narrative film. It’s a piece of video art,” McConnell says.

Scherlis (left) and McConnell repeatedly encountered an unexpected problem: information on the water cribs is highly regulated by the US government.

A fairytale of modern infrastructure

Six weeks later, in April 2023, Scherlis and McConnell have completed a script and a rough cut of the video that’s evolved significantly from their original conception. In early versions of the project, they planned to center the project on interviews with crib keepers. But in the end, the personal stories come through more indirectly: through research, found footage, and computer visualizations. “Something that we came up against over and over again was the lack of accessible records,” says McConnell, “a lot of which just seems to be around the questions of biosecurity the city has.”

Part of this transition is also due to a shift in the project’s goals. “We realized that what we wanted was to make something that takes people for whom thinking about infrastructure makes them totally glaze over, and pulls those people into an intense intimacy with the way that all this works,” says Scherlis. “We’re figuring out tactics for that, and I think that led us to move pretty far away from straightforward documentary.” The pair hopes to take the structures, which many Chicago residents may see every day, and “making them suddenly weird or engaging, approaching from an angle they didn’t feel like they were taking up in these ways of seeing the world that had become static,” says McConnell. “We want to bring people into this intimate relationship, and do it in a way that defamiliarizes them a little bit to the environment they may have grown numb to.” The goal is to make people think more deeply not only about the cribs, but about what they connect to—the water coming out of the tap, the infrastructure of the city, the complex and costly system of waste management that allows Chicago to function.

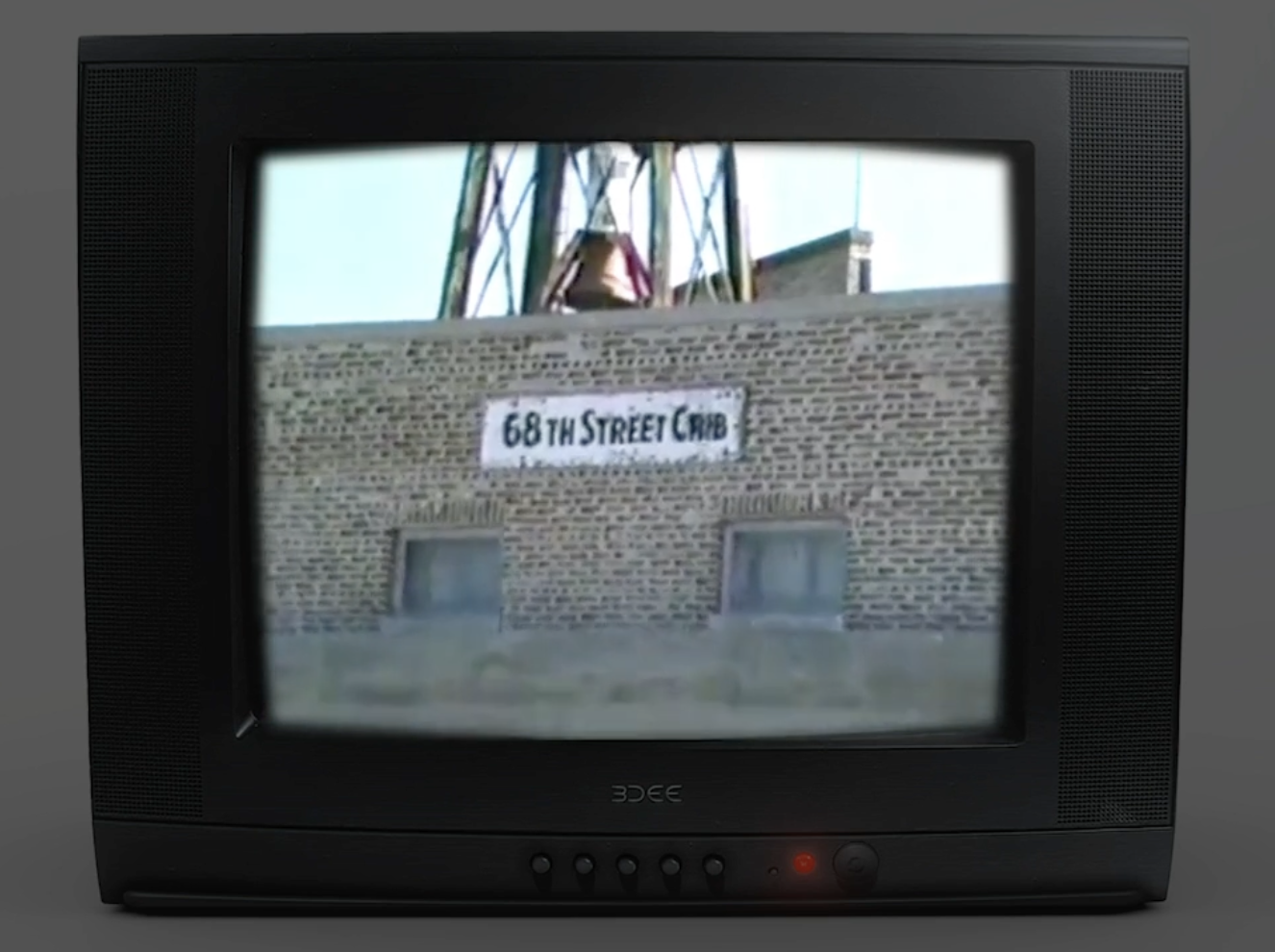

Views of the cribs from a WGN documentary series. The episodes present the cribs, and those that work on them, as oddities.

The final piece of the puzzle came via buried footage they were directed towards by a former crib employee. After months of looking, Scherlis was able to find and speak to an individual who had worked for the City of Chicago in the 1970s—not as a crib keeper, but as a crib painter. He provided details on life on the cribs (which, after policy shifted to stationing groups of workers together on the cribs, could be raucous) and pointed her to a series of WGN news reports from the 1980s and ’90s. In the videos, an interviewer travels to the cribs with a camera crew “and interviews the crib keepers as if they’re oddities,” Scherlis says. These videos include some of the only existing footage of the cribs and provide what is sometimes an uncomfortably intimate look into these workers’ bedrooms, pantries, and day-to-day lives. This is tied to an ongoing subject of McConnell’s study: the fraught political history of similar infrastructure sites that tend to be “put in a place that’s supposed to be far from where a lot of people live, or where the ‘right kind’ of people live,” she says. “There are these histories of geographical racism around certain kinds of industrial processes.” Emphasizing the way that these components of infrastructure tend to be buried, distanced, or put out to sea, Scherlis has pulled computer visualizations from the last few decades of similar hidden processes: a schematic of a nuclear waste plant, a corporate advertisement of a tunnel-boring machine, a tour of the human gut.

In a recent meeting, McConnell and Scherlis’ faculty advisor characterized their video as “a fairytale of modern infrastructure.” By using interconnected videos and ethnographic strategies less straightforward than a simple documentary approach, they have leaned into a mythical style of telling. “It’s almost like the way you would tell a child about these things,” says McConnell. “But then we were also thinking about that being a little bit demented.” And although it feels mythic, McConnell and Scherlis emphasize that it is very much a factual project. “We wanted to do a project that was scientifically and historically rigorous, but that didn’t look on its face like it was rigorous—that doesn’t quite show its iceberg,” says Scherlis. “We did very intensive research to figure out what actually happened, and then we narrativized that as if it’s myth. But it’s actually completely true.”

Approaches and refractions

The Graduate Collaboration Grants are based on the belief that the process of collaborating across disciplines is what leads to the most fruitful outcomes—academically, artistically, and personally. In the way the circumstances of the cribs themselves have resisted narrativization, McConnell and Scherlis have used the hybrid nature of the collaboration to transform the video into something that is neither pure ethnographic investigation nor video art, but an amalgamation of both. The challenges presented by the subject matter combined with the insights of their fields led to a result that could not possibly have existed otherwise. As they shifted from using direct ethnographic interview methods, McConnell says, “we started to think, how can we ask anthropological questions and pursue anthropological lines of inquiry without necessarily incorporating video of interviews or these specific techniques per se? So that’s been one big question: How do we explore the things that this social discipline is so focused on, without having it be as overt as we expected it to be in the beginning?”

The answer for the pair came through the collaboration itself, and through the complementary ways of thinking provided by their artistic and scientific practice. “In anthropology or even in academia in general, there’s certain ways of asking questions,” says McConnell. “And then in art, you’re doing something different. You’re not trying to explicate a theory. You’re not trying to give a single neat scientific answer.” The questions that the pair are interested in are deeply political, but the trick of the video, says Scherlis, is that the narrator withholds their perspective through the shield of an artistic lens. “It refuses to fall into didacticism,” she says. “It insists on being resistant to easy meanings in certain ways, even as it refracts the world in a way that I think we both see it. And I think that’s the point of making art for me.” McConnell too finds that the combination of artistic and anthropological approaches has allowed a multiplicity of potential answers to unfold in their collaboration. “I read a lot of fiction, and in thinking about what is a good novel to me, it doesn’t do the same work as an ethnographic,” she says. “How do we approach the same questions through art instead of through academic analysis? It’s been really cool to see.”

Scherlis (left) and McConnell hope their piece renders hidden infrastructure intimate and immediate.